Manifesto to LDC5, G20 and COP28 | Why the SDG Stimulus and a Marshall Fund for the energy transition must happen this year

Samoa graduated from a Least Developed Country to a Middle Income Country in 2014.

Titled “From Potential to Prosperity”, the 5th Conference for Least Developed Countries is about to begin in Doha, Qatar to review progress and identify solutions for the 46 LDCs to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. The contrast between the living standards of the 46 countries under review and the host country Qatar cannot be starker. The world has indeed grown profoundly unequal, a trend that the 2030 Agenda was meant to reverse.

The term Least Developed Country (LDC) was coined by the UN in 1971 at its 26th session of the General Assembly (UNGA), seven years after UNCTAD member States agreed that special attention was to be “paid to the less developed among the developing countries, as an effective means of ensuring sustained growth with equitable opportunity for each developing country”. The LDC criteria adopted by the UNGA in its resolution A/RES/26/2768 included the level of the Gross National Income per capita (GNI/capita), the Human Asset Index measured through nutrition, health, education, and the Economic Vulnerability Index. At the time, 25 countries had the lowest socio-economic indicators and were included in the LDC group: Afghanistan, Benin, Bhutan, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Chad, Ethiopia, Guinea, Haiti, Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Lesotho, Malawi, Maldives, Mali, Nepal, Niger, Rwanda, Samoa, Somalia, Sudan, Uganda, United Republic of Tanzania, Yemen.

From 1971 to 2012, another 27 countries were labeled LDCs, bringing the total to 52. From 1971 to 2022, only 6 countries graduated to Mid-Income status (MIC)- Vanuatu (2020), Equatorial Guinea (2017), Samoa (2014), Maldives (2011), Cabo Verde (2007) and Botswana (1994). And this despite intense efforts by the multilateral system to eliminate structural impediments faced by the LDCs. Progress has been modest despite those countries receiving close to a quarter of the total Official Development Assistance (ODA) over the last 50 years (24% to be precise).

According to the World Bank data, total ODA to LDCs from 1970 to 2021 amounted to USD 290,576,040,816.61. Yet, very few LDCs crossed the line to a MIC level. So, what’s happening? If you are looking for an answer, I suggest you read one of the most enlightening books in recent years on development economics written by Prof. Michael Spence- The Next Convergence: The Future of Economic Growth in a Multispeed World and published in 2011.

The book is the result of Prof. Spence’s work as chair of the Commission on Growth and Development at the World Bank from 2006 to 2010 and the conclusions he drew monitoring how countries grow.

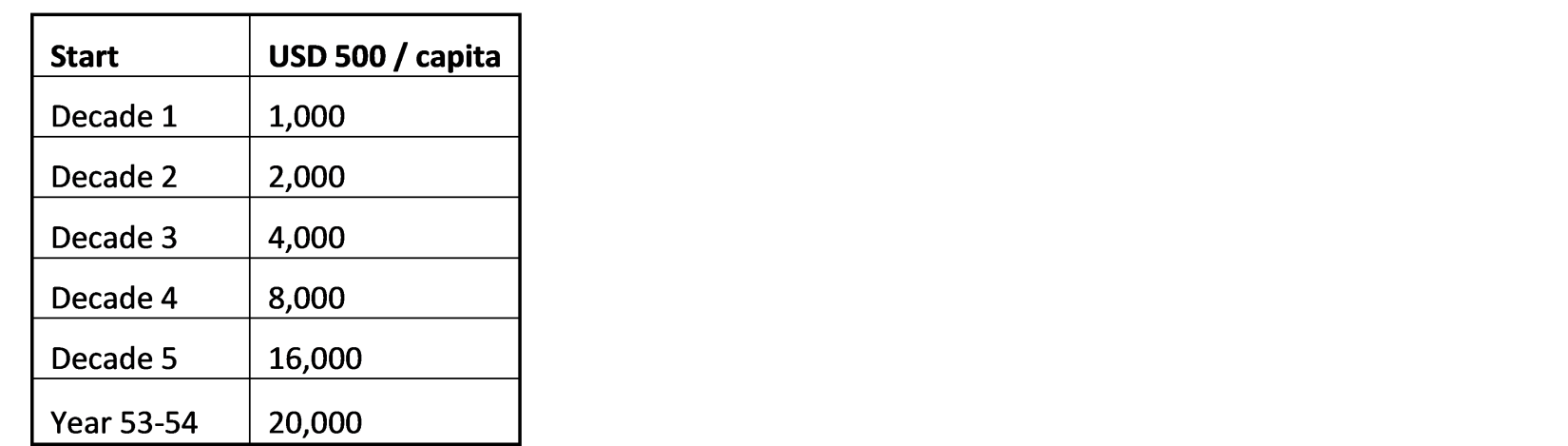

Table 1 – Time to double income per capita at 7% GDP growth rate per annum

Simply put it, to find out in how many years a country doubles its income per capita at a certain GDP growth rate, economists use the rule of 72. That is, for example, if a country maintains a 7% GDP annual growth rate, it will need 10 years to double its income per capita (72:7 = 10.03 years). For an LDC starting its journey in 1971 at a roughly USD 500 per capita, to reach the level of a High-Income country at a 7% GDP growth rate per year, it will need a little over 5 decades. But a 7% growth rate is quite high and very few countries have sustained such growth rates over years.

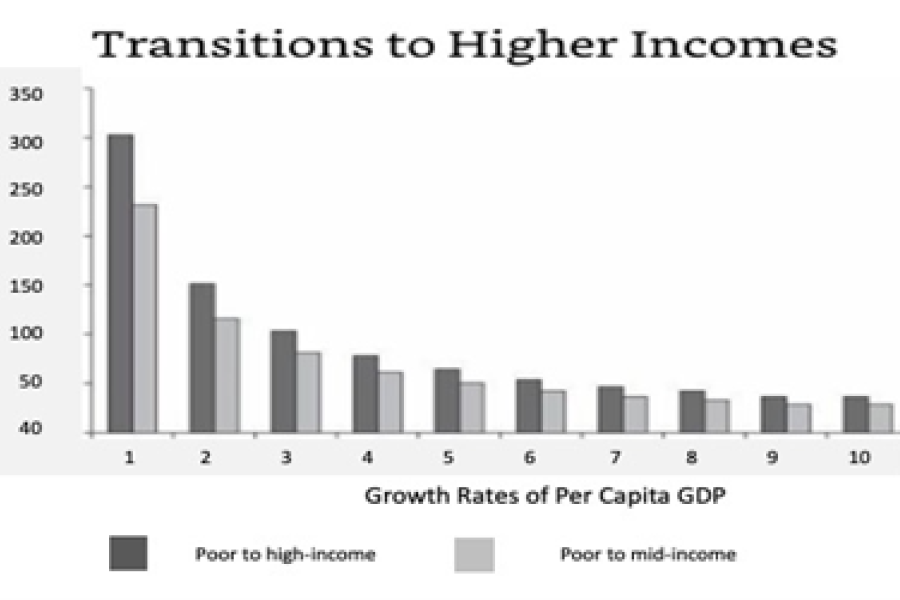

At different annual GDP growth rates, the number of years needed to move from an LDC to a Mid-Income or High-Income status is shown in Fig.1., again, using the simple rule of 72, which is applicable in system modeling if no big disruptions, crises, or shocks of magnitude happen, a very different reality than what we have experienced from the beginning of the 21st century.

In the current context in which estimated growth rates are below 4%, very few of the 46 LDCs will be able to graduate before 2030. No LDC could be expected to achieve its SDGs by 2030.

Figure 1 - Number of years per country to change income status

A simple example could demonstrate that Prof. Spence’s chart is very robust.

According to the World Bank data, the PPP-adjusted GDP per capita of Samoa increased from USD 2,688 in 1998 to USD 5,631 in 2017 growing at an average annual rate of 4%. The rule of 72 tells us that at a 4% GDP growth rate, a country needs around 18 years to double its income per capita, which is roughly what happened to Samoa from 1999 to 2017. The 2019 measles crisis and COVID-19 undid some of the progress the country has made, which led to the World Bank reclassifying Samoa as a lower-MIC in 2021.

A country like the Democratic Republic of Congo standing at USD 577/capita in 2021, which had a remarkable 10% growth rate in 2020, will need 7 years to double its income (USD 1,150/capita) and a total of 21 years to graduate to MIC (USD 4,600/capita) even if the 10% annual growth rate is maintained, a performance almost impossible to sustain under the present food, energy, and debt crises. At a more achievable rate of 4%, Congo would need more than 5 decades to become a MIC. While graduation per se is not the point, the income per capita must grow for people to live better lives.

All LDCs are highly dependent on ODAs and, to a large extent, their progress to date has been underpinned by development cooperation and globalization. At current levels of development financing, they will not be able to graduate by 2030, let alone to eradicate poverty and provide access to basic social services to all. It is therefore essential that, after more than 5 decades, rules governing the ODA and development financing more broadly finally change including the minimum contribution of OECD Development Assistance Committee members as well as the eligibility criteria for developing countries. For both the former and the latter, the UNGA is expected to adopt this year the Multidimensional Vulnerability Index to ensure development financing is tailored to country’s needs which the income per capita alone does not capture. But without a significant increase in available resources for developing countries to tap on, growth rates cannot be sustained at the necessary level to eliminate poverty. Earlier this year, the UN Secretary-General put forward the SDG Stimulus, a profound reform of development financing to enable the global system to overcome the impacts of compounding crises and achieve the SDGs. All we need is G20’s favorable consideration later this year under the presidency of India and a global commitment of the international financial institutions (IFIs) and developed countries to make it happen. The Stimulus aims to (1) tackle the high cost of debt and rising risks of debt distress, including by converting short-term high interest borrowing into long-term (more than 30 year) debt at lower interest rates; (2) massively scale up affordable long-term financing for development, especially through strengthening the multilateral development banks (MDB) capital base, improving the terms of their lending, and by aligning all financing flows with the SDGs; (3) expand contingency financing to countries in need, including by integrating disaster and pandemic clauses into all sovereign lending, and more automatically issue SDRs in times of crisis. The 46 LDCs will not be able to repay their debt under existing rules, nor will they afford the growingly expensive food and energy needed unless assisted by the IFIs and the multilateral development system.

But poverty is not the only challenge facing humanity and the LDCs most primarily. The existential threat posed by climate change will affect the long-term development potentials of all countries and significantly delay development progress in the LDCs. To mitigate and adapt to climate change, financial resources needed amount to USD 2-3 Trillions per year if we are to reach the net-zero target by 2050 and avoid a climate catastrophe. We look forward to solutions later this year in Abu Dhabi at COP28 to allow the Financial and Technology mechanisms under the UNFCCC to assist countries in building a more resilient future.

Both the G20 and COP#28 this year must deliver on pending commitments and unfulfilled promises. For the first time since the coming into being of the United Nations, the interplay of multiple crises may break the fragile foundation of global peace and stability, a frightening prospect that we can only avoid if we adjust course and ensure we grow together.